Home / Australia & South Pacific / Australia / Captain Bligh – History&…

Captain Bligh – History’s Most Misunderstood Globetrotter?

Those who owe everything they know about Captain William Bligh to Hollywood could be forgiven for thinking the man was a sociopath.

In many versions of the tale, the man whose leadership drove the crew of the HMS Bounty to mutiny is portrayed as a ruthless taskmaster, ready to flog or keelhaul the men under his command for the slightest infraction. The notion of Bligh ‘keelhauling’ anyone is particularly fantastic since this form of punishment, which saw a man hauled through the water under the keel of the ship, was a Dutch invention never practiced in the British Navy.

What transpired on the Bounty is just one chapter of Bligh’s story, one that for the most-part tells of an illustrious naval career and of a leader noted for his fairness and (for the era) clemency. Bligh’s temper however, frequently proved his Achilles Heel. The testimony of several Bounty mutineers sullied the Captain’s reputation and left him without work for eighteen months upon his return to London.

For those travelling through the South Pacific, particularly Tahiti and Sydney, the legacy of this misunderstood globetrotter can be keenly felt today.

Born in 1754, William Bligh’s Navy career began at age 7, as Captain’s Servant on the HMS Monmouth. The industrious young recruit served on several ships before catching the attention of Captain James Cook, the first European to set foot on the east coast of Australia. Cook offered Bligh a position as Master of the HMS Resolution, an appointment that at just 22 years of age put him ahead of many more senior officers.

It was fated to be Cook’s last voyage. Partnered with the HMS Discovery, the Resolution sailed for the Society Islands and Tahiti before turning north, bound for Alaska. But the expedition would inadvertently make the first European contact with the Hawaiian Islands, where a dispute with the natives would end in the deaths of Cook and four Marines. This tragedy however, led to Bligh proving himself one of the British Navy’s most skilled navigators, guiding the ships until they returned to Britain. On his return, Bligh would meet and marry Elizabeth Betham.

Subsequent voyages would take Bligh to the West Indies several times. Among his crew was a midshipman named Fletcher Christian, and while the two men soon became friends, their names would soon be forever linked and inked in history for much darker reasons.

Bligh took command of the HMS Bounty in 1787, appointing Christian as his Master’s Mate. The ship set out for Tahiti, with the goal of obtaining and transporting breadfruit trees to the Caribbean. Bligh’s attempts to round Cape Horn (still a challenge for recreational sailors today) would prove futile. After a month attempting to round South America, Bligh instead chose to approach Tahiti via Africa and Australia. While much easier, taking this route meant missing the breadfruit season. Faced with the horrific prospect of a five month stay in Tahiti (!) while the plants matured, the sailors struck up a warm relationship with the native Tahitians. A number of the men even took Tahitian wives.

Stories conflict as to what changed onboard the Bounty at this point to set the mutiny in motion. It’s possible that Bligh’s reluctance to deal out harsh punishments combined with the relaxed conditions of Tahitian living may have led to slackness among the less experienced members of the crew. A frustrated Bligh began to meter out harsher and harsher punishments to address the problem, but it was Fletcher Christian who would bear the brunt of his displeasure. Bligh was reported to fly into frequent rages, humiliating or berating his Master’s Mate for seemingly minor mistakes.

Just 23 days after leaving Tahiti, Bligh was surprised in his cabin by Christian and 18 other mutineers (not the ‘majority’ of the crew as commonly claimed). The mutiny was quick and bloodless, setting Bligh and most of his loyal men adrift in a 23 foot launch with only a week’s supply of food, the most basic navigational equipment and no sea charts. Again, Bligh would demonstrate his skills as a navigator, reaching Timor after a 47-day voyage, during which time his men lived on just 1/12 of a pound of bread per day (equivalent to about one slice). As they sailed up the Australian east coast, Bligh took the opportunity to sketch maps of the islands dotting the Great Barrier Reef.

Having lost his ship, Bligh faced a court-martial on return to England. He would nonetheless secure pardons for several loyal crewmen on trial for the mutiny. With little room in the small boat, these men had been forced to stay behind on the Bounty, only to be later charged with the mutiny since the law made no distinction. Bligh was exonerated by the court and given command of the HMS Providence. Joining another vessel, he again embarked on a voyage to bring breadfruit to the West Indies, an expedition that was this time successful.

Bligh’s reputation however, was not so easily repaired. The testimonies of several men tried for the mutiny made Bligh’s short temper and overbearing command style public knowledge. In 1797, Bligh served as captain of the HMS Director, only to have another mutiny on his hands. The fact that this was part of a Navy-wide dispute that had little to do with Bligh himself, or the conditions onboard the Director, did not stop the spread of his unfortunate nickname ‘that Bounty bastard.’

William Bligh’s military career however, would be untarnished by this reputation. If anything, he became noted as a firm disciplinarian, and was eventually offered the Governorship of New South Wales. Charged with bringing the rowdy colony to heel, Bligh became its fourth Governor on his arrival in Sydney in 1806.

He would hold the post for barely two years.

Having grown stricter over time and more abrasive in his bearing, Bligh soon made new adversaries of wealthy and influential settlers such as wool entrepreneur John Macarthur and much of the New South Wales Army Corps. In his efforts to enforce the crown’s regulations preventing private trading, Bligh infuriated the colony under his charge. Once again, Bligh’s unwillingness to turn stern words into action may have proved his undoing, for he refused to suspend his judge-advocate Richard Atkins, despite Atkins’ frequent lapses of competence. He instead turned to legal actions against Macarthur, who responded by painting Bligh as a brutal tyrant. The influential Macarthur’s account stuck, and Bligh’s term as Governor came to a swift end when 400 soldiers marched on Sydney’s Government House and arrested him.

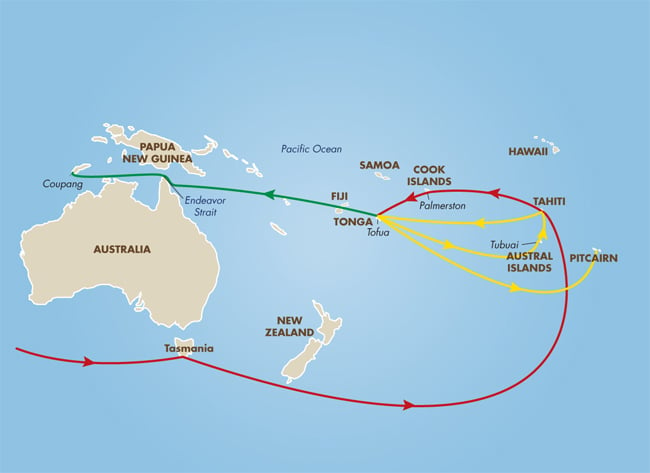

■ Movements of Bounty after the mutiny, under Christian’s command

■ Course of Bligh’s open-boat journey to Coupang (Timor)

Along with Sir Ernest Shackleton, Bligh is credited with one of the two most extraordinary feats of seamanship in an open boat. With 18 loyal crew, Bligh navigated the 23foot (7m) launch on a 47 day voyage to Timor in the Dutch East Indies, equipped with a quadrant and pocket watch, and without charts and a compass. He recorded the distance as 3618 nautical miles (6701km/4164mi).

Death by starvation was a constant threat. For fresh water, luckily it rained most of the time. One crew member died during the voyage, stoned to death by natives in Tofua when trying to augment their meager provisions. They were also chased by cannibals in what is now known as Bligh Water, Fiji.

Taking refuge in Hobart, Bligh attempted to muster the support needed to regain his position, but the damage had been done. Bligh’s name would be synonymous in New South Wales with cowardice and behaviour ‘unbefitting a gentleman’ for years to follow. Still, the troubled governor’s mark on Australia is remembered to this day in the form of a bronze statue in Cadmans Reserve at Circular Quay (Sydney Harbour). The statue even preserves the scar on Bligh’s face, though stories claiming this was the result of a childhood axe-throwing accident are unsubstantiated.

Separating fact from myth is a recurring theme when looking at the life of William Bligh. Painted in popular culture as a tyrannical commander and rejected in Australia for his high-handedness, it would be easy to overlook Bligh’s numerous achievements. The Royal Navy however, did not. Though twice more faced with court-martial, Bligh was acquitted on both occasions and promoted to Rear Admiral, then eventually Vice-Admiral on his return to England in 1814. He died peacefully three years later in Farningham, Kent.

Today, William Bligh is regarded as one of the finest navigators in British naval history. He is credited with fostering cordial relations between the Navy and the Tahitians, as well as bringing breadfruit to the West Indies, where it remains a popular food. Among his more prominent descendents is former Queensland Premier Anna Bligh.

Get more travel inspiration by email.

Subscribe

0 Comments

Get the latest travel trends & hear about the best deals on vacations around the world.

If you’re a Globetrotter, these are the newsletters for you!